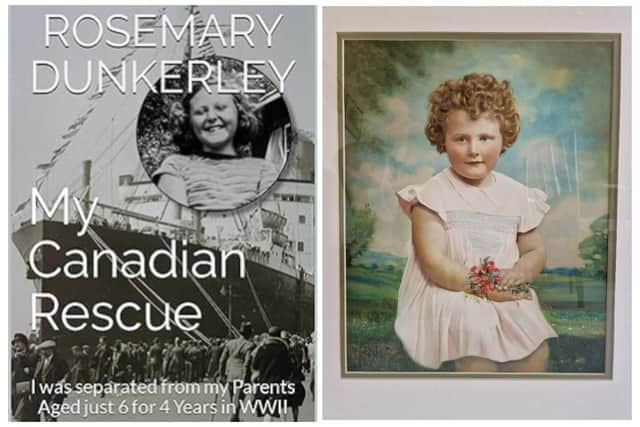

90-year-old Bretton author pens touching book about being evacuated to Canada as a child during Second World War

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

and live on Freeview channel 276

A Peterborough lady has released a touching book recalling her emotional time as an evacuee in Canada during the Second World War.

Already available on Kindle, My Canadian Rescue is also due to be launched in hardback form shortly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad90-year-old Rosemary Dunkerley was just six years old when she was sent to Canada by her parents following the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

Speaking to the Peterborough Telegraph at her toasty warm Bretton home, Rosemary recalls how the decision to send her away was “almost certainly” the result of her father Norman’s previous combat experiences.

“My father had fought in the First World War and he was horrified,” she says: “he had horrible memories.”

When Norman found out an order of Anglican nuns at a convent in the family’s home town of Whitby were making arrangements to evacuate local children, he immediately contacted the Mother Superior.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter first being evacuated to a country estate in County Durham – which Rosemary remembers as “a quite horrible place,” – the nuns were given the option of taking the children to Canada.

Norman, who was the treasurer of Whitby, was keen for his only daughter to join them.

While Rosemary remembers how the decision made her parents felt “awful” she believes her tender age actually worked in her favour:“I think I was just too young to understand the situation,” she says.

“And anyway, I thought ‘we’ll be going home in six months’ time,’ and that calmed me.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe nuns, children and families all believed that the arrangement would last for just half-a-year.

Little did they know that it would be four years until they would see eachother again.

Deadly Nazi U-boats

“In the middle of July, we set off in a boat [from Liverpool] called the Duchess of Bedford,” Rosemary recalls.

The ship was to travel to Canada as part of a convoy, a tactic used to help keep vessels safe from the deadly Nazi U-boat ‘wolfpacks’ which hunted Allied shipping in the North Atlantic with impunity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile Rosemary’s ship made the trip to Canada safely, a follow-up vessel was not so fortunate.

“Another boatload of evacuees was torpedoed,” Rosemary recounts: “It sank with all those little children on it.”

Following 17 days at sea, the Duchess of Bedford finally arrived in the city of Montreal, Quebec.

The delighted six-year old was immediately wowed by the friendliness of Canadians.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They were amazing,” she says: “They opened their doors to us and looked after us.”

Rosemary was temporarily billeted with a local family while the nuns finalised the arrangements for establishing a new convent school within the area.

She remembers the family’s mum very well.“I was taken into her home and she treated me beautifully,” she says.

“She had two little children my age.”

After about six weeks, the seven nuns and 70 children moved to a property near Toronto, Ontario called Erindale Hall.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was a very beautiful house; quite modern and even had a swimming pool.”

While Rosemary liked her new ‘home’ she was less enthused by the nuns’ “odd” style of school teaching.

“It was extremely boring; but we were safe, which was the main thing.”

Fond memories

All of the children stayed with a foster family during the school holidays.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome of Rosemary’s fondest memories came from her staying with the Salter family on their isolated farm near Oakville, a small village (then) on the outskirts of Toronto.

“They looked after me every school holiday - whenever a school holiday came, I went to Oakville,” she remembers.

Rosemary became completely enamoured with Mrs Salter, who she called ‘Auntie Jean’, and became firm friends with her teenage daughter, Joanne.

“They really loved me,” she says.

Exercising amazing powers of recall, Rosemary recounts how Jean used to write reassuring letters home to her mum and dad in England:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“She would write long, long letters - but they never said anything nasty about me; everything about me was good.”

Rosemary’s anguished ‘mummy’ used to write back frequently.

“Mummy wrote most of the letters, and she would send parcels at Christmas and birthdays.”

When Rosemary was back at the convent, it was one of the younger nuns, Sister Bridget Mary, who used to write home on her behalf.

“She used to write to my mother every month,” she says: “she did that for all of us.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany of these letters, some of them extremely poignant, are in Rosemary’s book.

Their inclusion, along with period documents and newspaper cuttings, really help to bring that period of history – and Rosemary’s journey – to life.

As the years passed, the little English girl grew up happily in the safe and friendly surroundings of her foster country.

Wandering around rural villages, exploring the city of Toronto, swimming in Lake Ontario and kayaking at Camp Muskoka (“a very calm place”) were some of the youngsters favourite things to do.

And then, in 1944, everything changed very quickly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA disastrous journey

“I was getting ready to go up to Camp Muskoka when we were all taken back to the school,” Rosemary explains.

“Within a few weeks we were all on a boat.”

By this time, the tide of the war had turned dramatically.

Britain, outside of London and the southeast of England, was now considered a relatively safe place to be.

After four years of being a welcome guest of Canada, Rosemary was on her way home.

The now ten-year-old experienced mixed emotions, but knew she would dearly miss the country she had come to call home.

“All of the Canadians were very kind to me,” she laments.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnfortunately, Rosemary’s sea journey home across the Atlantic was to prove disastrous.

Once again, the vessel she and her fellow evacuees were billeted on – the New Zealand registered Rikki-Tikki-Tavi – set sail as part of a convoy.

Even at this stage of the war, Nazi U-boats were still lurking in the depths of the North Atlantic.

“Our boat broke down,” Rosemary remembers, wincing at the memory.

“It was very serious - the convoy had to leave us behind.”

What followed was the longest 24 hours of Rosemary’s life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The boat had to be kept absolutely silent, and we were forced to wear our life jackets all the time; we even had to sleep in them.”

“It was very, very eerie - you could just hear the sound of a bell ringing.”

Rosemary closes her eyes as she dwells on the 80-year-old memory:

“It only lasted 24 hours - but it lasted on my brain forever.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter what seemed like a lifetime, the Rikki-Tikki-Tavi received repairs and continued on its way, finally docking in Liverpool 17 days later.

Rosemary has been measured and adept in recalling her experiences during our interview.

It is only now, remembering the moment she disembarked at Liverpool Docks in 1944, that her voice begins to crack a little.

“I remember walking down a metal tunnel and coming towards me were two old people, arm-in-arm.”

“I didn’t recognise them.”

“It was my parents.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA unique time in British and Canadian history

It has taken Rosemary three years to put this book together.

The dedicated 90-year-old, who used to be a teacher for many years, initially intended the undertaking to be nothing more than a family history project.

However, this all changed when she got in touch with Canadian historians to see if they had any documents relating to that time.

“Their reply was ‘we’ve got nothing’ - I was shocked!”

This inspired Rosemary, ably assisted by her son Andrew, to dig out, organise and compile an accurate account of that unique time in British and Canadian history for posterity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile she is keen for her own family to know about her past, Rosemary’s chief aim with this project is to help ensure Canada – and the wonderful Canadians who ‘rescued’ her – receive the credit they deserve.

“I want people to know how good the Canadians were to us,” she says, adding: “they seem to have been ignored.”

As well as publishing My Canadian Rescue, Rosemary has also arranged for many of the documents, cuttings, and letters featured in the book to be displayed in a Toronto museum.

Sitting at her dining room table with her well-fussed cat brushing her feet, the sharp-as-a-tack 90-year-old sums up how she feels about finally being able to put her story, and her undying gratitude, into words.

“I’m very pleased,” she says, then adds – with typical Blitz spirit – “Now, how about a cup of tea?”